At the intersection of East and West, tradition and innovation, the Taishō period (1912–1926) saw the emergence of bold new kimono styles that reflected Japan’s rapidly changing society. Known as Taishō Roman, this aesthetic blended romantic ideals, Western influences, and a playful reinterpretation of traditional dress. In this article, I revisit a demonstration I co-hosted with Sonoe Sugawara of Furuki Yo-Kimono Vintage, where we introduced the unique look of the Taishō Roman schoolgirl, complete with high-collared blouses, red hakama, and vibrant, eye-catching kimono.

This article is 860 words long.

🕒 Estimated reading time: 4–5 minutes.

At the Yokimono Japanese Christmas Market in December 2022, I collaborated with my good friend Sonoe Sugawara of Furuki Yo-Kimono Vintage on a demonstration and talk of Taisho period kimono styles. This turbulent era gave birth to some eclectic kimono styles which were based on a new approach towards Japanese and Western modes of dress. One of the styles we introduced was the Taisho Roman (大正ロマン) style of female students.

Sonoe demonstrated how to recreate the so-called ‘Taisho Roman‘ style, also known as the hai-kara style, with a 1920s silver and purple vintage kimono and red hakama from her shop.

In general, Taisho Roman (大正浪漫, or 大正ロマン) refers to the ideals of romanticism which were expressed by a quirky reinterpretation of traditional culture during this time. Kimono of this decade often featured flowing, asymmetrical designs, with playful and whimsical motifs such as flowers, birds, and butterflies. It was also common to see the use of luxurious fabrics such as silk and satin, and the incorporation of Western-style elements such as lace and embroidery. The Taisho Roman kimono style became known for its bright colours and bold, graphic patterns such as the yabane (矢羽, arrow feathers) pattern.

The word hai-kara (ハイカラー) derives from the word ‘high collar’ on the other hand and refers to the, for Japanese eyes, unusual collar style of shirts of this time. Victorian-style blouses became popular with young Japanese women of the middle class who wore these as undergarments, with the collar and cuffs peaking out under the kimono. The term also more generally meant ‘to dress in the latest western fashion‘ which demonstrates the fashion-forward way of thinking of these young women.

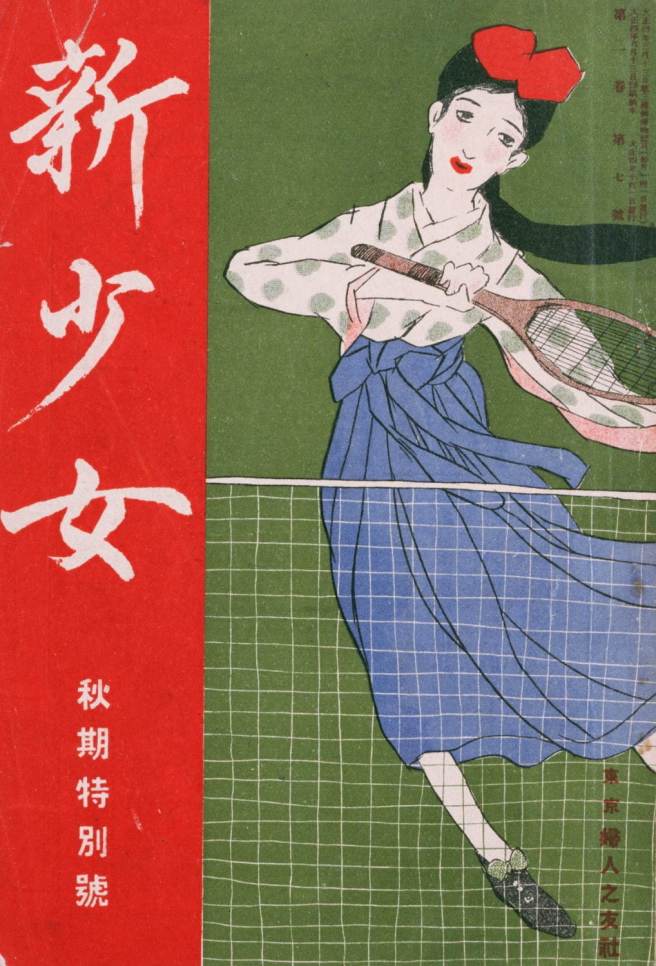

Besides blouses, women started to adopt hakama which were previously exclusively reserved for men. With more women entering education, female students were in need of a uniform which allowed them to participate in all school activities on the same level as the boys. Debates on movement and the body resulted in the decision to modify men‘s hakama trousers by turning them into hakama skirts for young women.

© Ōta Memorial Museum of Art (太田記念美術館), Tokyo.

This hakama style was considered to allow for unrestricted movements of the hip and legs. This was particular important in a time when physical education became part of the school curriculum, and sports of all kinds became popular leisure activities. Shoes also played a part in this, with the traditional sandal footwear of geta being replaced by lace shoes and boots. The new mode of transportation, the bicycle, became favoured and later representative of the forward-thinking young men and women who were considered to built a bright future for the Japanese nation.

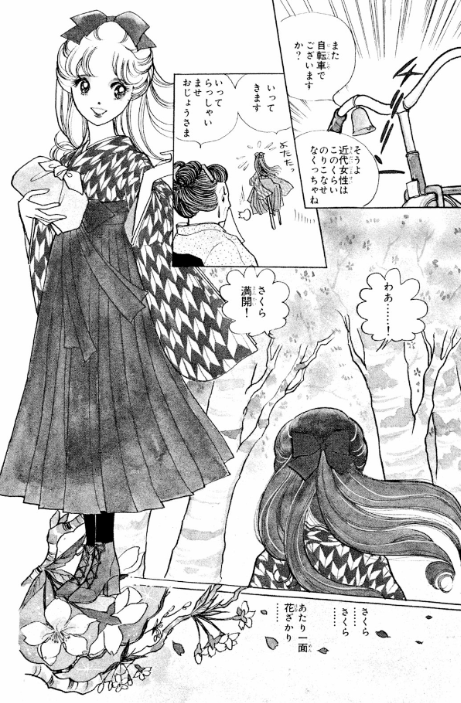

Another popular reference of the style is the manga Haikara-San: Here Comes Miss Modern (はいからさんが通る haikara-san ga tōru, 1975-77) by Waki Yamato. The manga that tells the story of Benio Hanamura, a young woman living in Tokyo in the 20th century. Benio is laballed as a ‘tomboy‘ with a big interest in Western culture and fashion. This sets her apart from and often creates a conflict with the more conservative Japanese women of her time. As a female student, she often wears a yabane-patterned furisode kimono and hakama combination as depicted below.

Overall, the Taisho Roman kimono style was a reflection of the era’s fascination with modernity, individualism, and self-expression, and represented a departure from the more rigid and feminine conservative styles that had come before it.