It just recently occured to me that I never talked about my appearance on TV Tokyo’s well-known show Why Did YOU Come to Japan? (YOUは何しに日本へ?) on this blog. I’m not quite sure what kept me from writing about it before, but here is me aiming to change that.

This article is 720 words long.

🕒 Estimated reading time: 4 minutes.

For those unfamiliar with the show, Why Did YOU Come to Japan? follows the journeys of international visitors to Japan, often starting with spontaneous interviews at the airport. The programme’s crew approaches travelers to ask about their plans, hoping to uncover unique and meaningful stories.

I was one such traveler, approached by the crew at Kansai Airport in February 2018, just as I was arriving for a six-month stay to conduct PhD fieldwork. The crew followed me over three full days, capturing glimpses of my daily life as a researcher in Japan. While many scenes didn’t make the final cut, the broadcast focused on my research visit to the shop MIYABI in Kitakyushu.

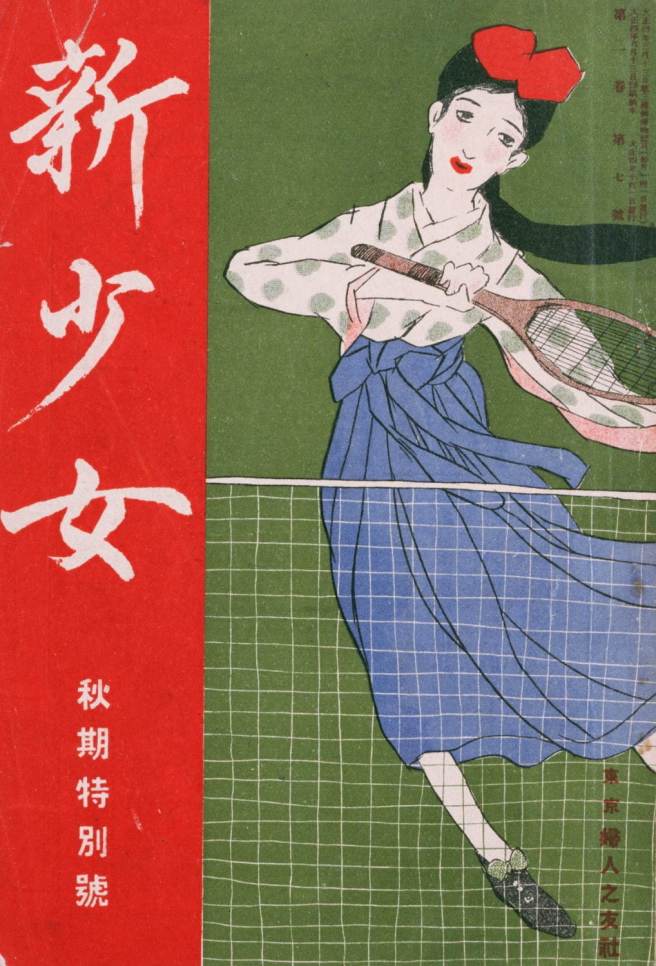

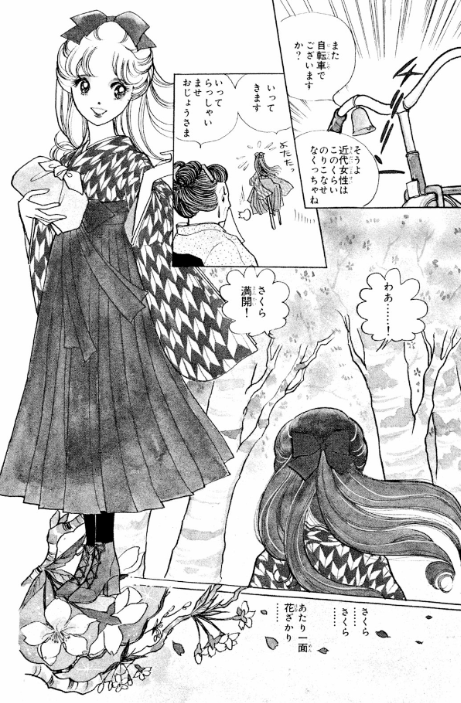

The shop MIYABI is renowned in Kitakyushu as a popular destination for the local Seijin-Shiki (成人式), or Coming-of-Age Ceremony. This annual event celebrates young adults reaching the age of then 20, now 18, marking their transition to adulthood. Kitakyushu’s ceremony, in particular, is famous across Japan for its attendees’ incredibly inventive attire—each year, many invest a significant amount into crafting unforgettable outfits that reflect personal style and hometown pride.

Although I didn’t get to attend the ceremony itself or interview the young adults firsthand, my visit to MIYABI provided valuable insight into these unique local customs. The shop’s owner, Miyabi Ikeda, shared stories of her experiences and the elaborate preparations that go into helping customers create statement outfits for this important day. Through her perspective, I gained a deeper appreciation for the cultural significance and creativity surrounding Kitakyushu’s Coming-of-Age Ceremony.

The distinctive styles of the hade hakama (派手袴) for men and oiran kitsuke (花魁着け) for women served as key inspirations for Chapter 6 of my PhD dissertation, Challenging Normative Gender Ideals? Alternative Forms of Coming-of-Age Dress. In this chapter, I examine how these bold styles transcend conventional norms to allow unique expressions of identity. For those interested, my full dissertation can be accessed here: Becke, Carolin (2022) Negotiating Gendered Identities Through Dress: Kimono at the Coming-of-age Day in Contemporary Japan.

A summary of the TV episode discussing these styles is also available in Japanese on the programme’s website: Why Did YOU Come to Japan? – Episode 180730. For a closer look at MIYABI’s most recent creations, I recommend following their Instagram account: @miyabi_kokura.

Reflecting on this experience, I’m reminded of how unexpected encounters can shape and enrich our journeys in ways we don’t anticipate. Being part of Why Did YOU Come to Japan? gave me a unique opportunity to share my research with a broader audience and connect with Japan from a new perspective. It captured not only the purpose of my fieldwork but also the warmth and curiosity that I encountered throughout my time there. I hope this glimpse into my journey offers you some insight into the fascinating intersections of research, culture, and the unexpected surprises that make travel so rewarding.